triptych

a story of inheritances

pyramidion

The pyramids of Egypt were not always as they are today, rough and crumbling amid lone and level sands. When first built by curiously technologically-advanced Egyptians, the massive structures were covered in gleaming limestone, immaculately smooth and flawlessly fit. Atop each pyramid was a pyramidion, a perfectly symmetrical capstone etched with arcane symbols and leafed in gold or electrum.

Few pyramidia survive to this day.

What happened to the pyramids?

It was not simple environmental damage, nor neglect. The xeric Gaza plateau is almost ideal for the preservation of stone structures, and mounds of stone require little upkeep. Nor was it simple vandalism, apocryphal stories about Napoleonic legionary cannon notwithstanding. Rather, the pyramids were plundered.

Being a cheap and convenient source of costly materials, future despots stripped them bare: first the gold foil, then the polished casings. Much of the Great Pyramid’s limestone survives in the renowned Mosque-Madrasa of an-Nasir Hasan, a fourteenth century Mamluk. Muhammad Ali Pasha al-Mas'ud ibn Agha, Egypt’s Ottoman governor in the mid-nineteenth century, took what remained for his Alabaster Mosque.

city of marble

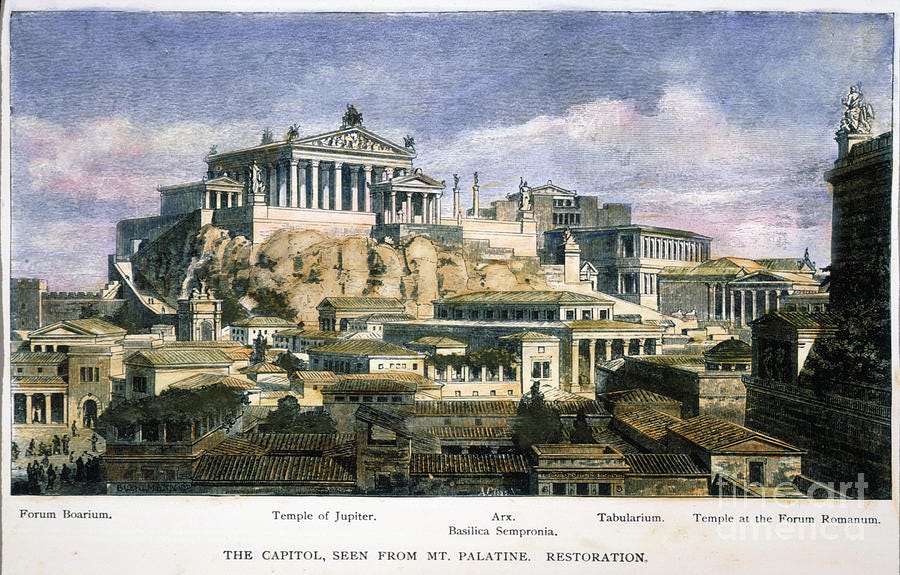

Augustus boasted that he turned Rome’s bricks to marble. So it seems from our reconstructions and projections from extant ruins. The Romans did many things, but first and foremost they built. I don’t know whether the modern engineering profession traces its roots to a Roman tradition, but I hope we did not abandon this heritage.

But all that remains of Rome is ruins; the best-known fact about Rome is that it fell. The most famous edition of Gibbon represents the declining nation on its spines as a crumbling pillar.

As Rome declined in the West, the population of the city collapsed, falling from a peak of 1.5 million souls to fewer than twenty thousand. The pillars and monuments were neglected when they were not razed, and the Colosseum became pastureland. Later famously, it was a botanical marvel, as dozens of foreign plants had taken root after their seeds traveled to the arena in the fur of exotic animals killed for sport in Antiquity.

As in Egypt, marble was sometimes taken for new projects, but here continuously and for millennia (starting even before the city’s sack). Prettily, splinters of colored marbles were repurposed for the manufacture of stained glass. Less-fortunate columns and statues were reduced by limeburners to make mortar, transmuting the marble city once more to brick.

subdivision

Summit Avenue in Saint Paul, Minnesota, was once the preserve of that city’s class of late 19th century plutocrats: lumber barons, railroad tycoons, and dry goods nabobs. The nation had not yet become culturally unified, and local elites still held sway in their regions in a sort of social feudalism. The great men of the North displayed their stature by competing with one another at building mansions.

The results were at turns spectacular and crassly ostentatious. Tudors sat next to Victorian homes abutting Neoclassical gems, with occasional spires rising amid smokestacks. The almost-upper crust of the city that could not afford such displays built on streets nearby Summit, Grand and Portland and Iglehart, the architectural-mercantile Off Broadway. Even these homes are lovely.

Climate control was provided by new boilers, a marvel of the second industrial revolution that distributed heat in radiators. They’re still a more pleasant way to warm your house than forced air.

The best floor to have was oak; it was expensive, so you used it on the main floor in common areas. In the bedrooms upstairs, you economized with maple. Fir was the poor man’s flooring despite its beautiful coloring, because it was easily damaged and prone to splintering. Woodwork was sometimes exposed, but often meant to be painted over.

In the way that Americans in the 1950s were mad for their new cars, the society of Saint Paul in the Gilded Age reveled in their modern homes.

Recently we looked at homes in the Summit area. Not on Summit proper, to be clear—we’re not high rollers. Ultimately, we came away empty-handed, and turned our search elsewhere. We found several problems.

First, some of the houses were in sufficiently bad repair that restoring them to sound condition would be prohibitively expensive or time-consuming.

Second, many of the homes had been disfigured by misguided later owners. On the mild end, one Victorian home had an architecturally-incongruous porch appended. At the extreme, a (small) mansion with a (small) grand stairway in what used to be a prime location had been rendered unrecognizable as a home of good repute by an occupant in the 1970s who (judging by signage) called himself “Honcho” and had a penchant for covering whole wings in cheap wood paneling.12

Finally, many once-loved homes have been subdivided and converted to rental slum housing, complete with crustpunk decor and stencil graffiti. We decided not to tour one suspiciously-inexpensive multiunit conversion after we noticed that in some photos the ceiling appeared to be held in place by a two by four and nails.

What happened? It’s hard to say, because every history of Summit Avenue (and indeed of Saint Paul) I’ve come across with a few quick Google searches comes to an end after the 1920s. Make of that what you will.

I can tell a story from recollections: America fled to the suburbs and cities became hollowed haunts. Rondo Street, the middle-class black neighborhood just to the north, was razed to make way for I94’s course through the city. Jobs and money flowed to suburbs like Maplewood, where 3M was headquartered, and the federal government siphoned power from the Minnesotan capitol. Society left Saint Paul and the people who live in the old homes are not of the same order as the ones who built them.

Aggressive action by the city government preserved most of the original architecture on Summit itself; 373 of the peak 440 structures can still be seen. The surrounding streets of the merely well-to-do that we toured were pointedly excluded from regulatory protection and have not fared as well.

A secret underground order of Summit Avenue revanchists exists. They frequently become real estate agents, hoping for wealthy clientele, praying they take interest in a Summit home: not for the agency fee, but to walk the halls of the homes they love and know by name, and tell their stories to someone who might understand them.

I’m obscuring details and tweaking facts here because I don’t want to have bad blood with the kind people who let me view these houses; but the essence of the truth is maintained in this paragraph. You’ll just have to trust that I couldn’t come up with this story without observing a comparable case.

Also, please let me know if I might get sued for this paragraph.

love this writing robot!!!

Great writing and ideas. Love it